‘Annie Live!’ has ‘hard knock’ time getting off the ground, but sprawling versatile set stands out

Subscribe to NCS for the latest news, project case studies and product announcements in broadcast technology, creative design and engineering delivered to your inbox.

After sitting out a while due to the pandemic, NBC brought back the live TV musical with “Annie Live!,” a production that was rather daring in its scenic scale — perhaps to its own detriment.

The live broadcast, which was shot on a sprawling stage in Long Island, suffered from multiple production issues throughout the first half or so of the three hour airtime.

Action was often captured by out of focus cameras or ones that appeared to struggle to maintain smooth movement.

There was also heavy use of jibs and handheld cameras, but often these appeared to struggle to keep up with the action — and there were some oddly framed shots that popped up here and there.

In this story, screen captures, indicated by the NBC “live” bug in the lower left, were taken from the live telecast as aired in the Chicago market.

Other photography was provided by NBC and it’s not clear if these were shot during a rehearsal or photoshoot, so they may not match exactly what aired.

Like with most of the live musical productions of the past, other cameras, crew members or performers often popped up unintentionally on the edge of shots as well, as shown here.

The musical got off to a murky start thanks to the opening scenes being at night.

Nighttime scenes, including both the opening number and when Annie visits a shantytown, perhaps could have made the light “come out” a bit more rather than waiting until “tomorrow.”

While it’s obviously dark at night in real life, there were times when cameras were pointed at a person speaking or singing who was either nearly invisible or almost completely in shadow or silhouette, which, if on purpose, was an interesting choice.

At other times, characters in the same scene were lit much better — making the differences a bit glaring.

It’s not clear if this issue was due to missed lighting cues, actors or scenery not being on the correct marks or some other issue.

In fairness, there’s a lyric in “Hard Knock Life” that says “Don’t it seem like there’s never any light?” so the low lighting very well may have been a creative decision meant to show off how dreary life was like in a Depression era orphanage.

It’s also worth noting that different televisions and settings can cause images to display pictures differently, but the “Annie Live!” lighting seems to attempt to walk the fine line between too dark and too light — and perhaps tipping more toward the dark side a bit.

Part of that may have been due to how the production was staged — there was a small audience area set on one side of the stage at Gold Coast Studios in Bethpage, New York.

The rest of the voluminous space was dedicated to creating multiple staging areas for the show itself, meaning that at least some of the cameras were likely set up far from the actors, making it more difficult to find and keep focus, especially given the dark lighting used at times. Extreme “zoom ins” also amplify an unsteady camera’s “wobbling” exponentially.

Wrapping around most of the performance area was a large faux brick wall with a scaled down version of the Manhattan skyline circa 1933 with color changing backlight integrated into it depicting lit buildings, including what appears to the Empire State Building. Above and around this was a purposefully rough scenic element that appeared to be made of irregularly stacked faux brick evocative of a cave opening.

This mean the “sky” was essentially made of faux brick — an interesting juxtaposition in terms of texture.

Depending on the lighting cue and tightness of a shot, the texture of the brick was more visible at times, but it, combined with the “imperfections” and grittiness of other scenic was a gave nod to the rough times the musical is set in.

New York City got another nod thanks to the monochromatic map of the island of Manhattan sprawled out on the floor of the stage.

Meanwhile, an elevated train track wrapped around stage right with a large circular element that could be lit as either the sun or moon.

Many scenes leveraged the city skyline background as a prominent element, with numerous lighting effects and cues, as either a primary or distant background.

For early scenes in the orphanage, columns were brought in and domed lights flew in from above and a single elevated freestanding doorway was placed in the center — a common design element in the production — creating a deep, layered look that gave the feeling of an enclosed room even though it was still open to the skyline behind and no actual walls were present.

For scenes in Miss Hannigan’s office, segments of walls were brought in to create the feeling of a more enclosed space, with the freestanding door element making another appearance.

One wall appeared to be blocking to view of at least a part of the studio audience, though it’s likely there were return monitors set up for them to watch the action.

This was similar to how Daddy Warbucks’ office at his mansion was filmed — with segments featuring walls, doors and windows brought in but with gaps left between them that created “blinds” for cameras to capture the actors from a variety of angles in a way that’s similar to how many roundtable news programs are shot (in at least once case, however, a crew member stepped a bit too far forward and was caught by the edge of the lighting).

Other scenes or portions of larger scenes were placed in the open areas closer to the audience area and often shot tighter.

What appears to be a crew member is visible in the upper left of this screenshot.

This was in stark contrast to the foyer of the mansion, which featured a freestanding staircase element with door at the top — which, at one point, was traversed by a camera, giving the TV audience a “flipped” view of the stage.

The foyer space also boasted multiple archways that spilled down from the elevated doorway, which, like the one used for orphanage scenes, was arched, which appears to be a primary motif in the design, perhaps a nod to the wraparound cityscape background.

Another unfortunate incident was when Harry Connick Jr. and the bald cap that’s been widely mocked on social media made his first entrance as Daddy Warbucks, but most of his face was covered by NBC’s content advisory label that was displayed because the broadcast had just returned from a break.

Since it was Connick’s first scene, his entrance got an applause by the studio audience, but at first it wasn’t clear who they were clapping for — until someone wisely (or luckily) cut to a closer shot of him.

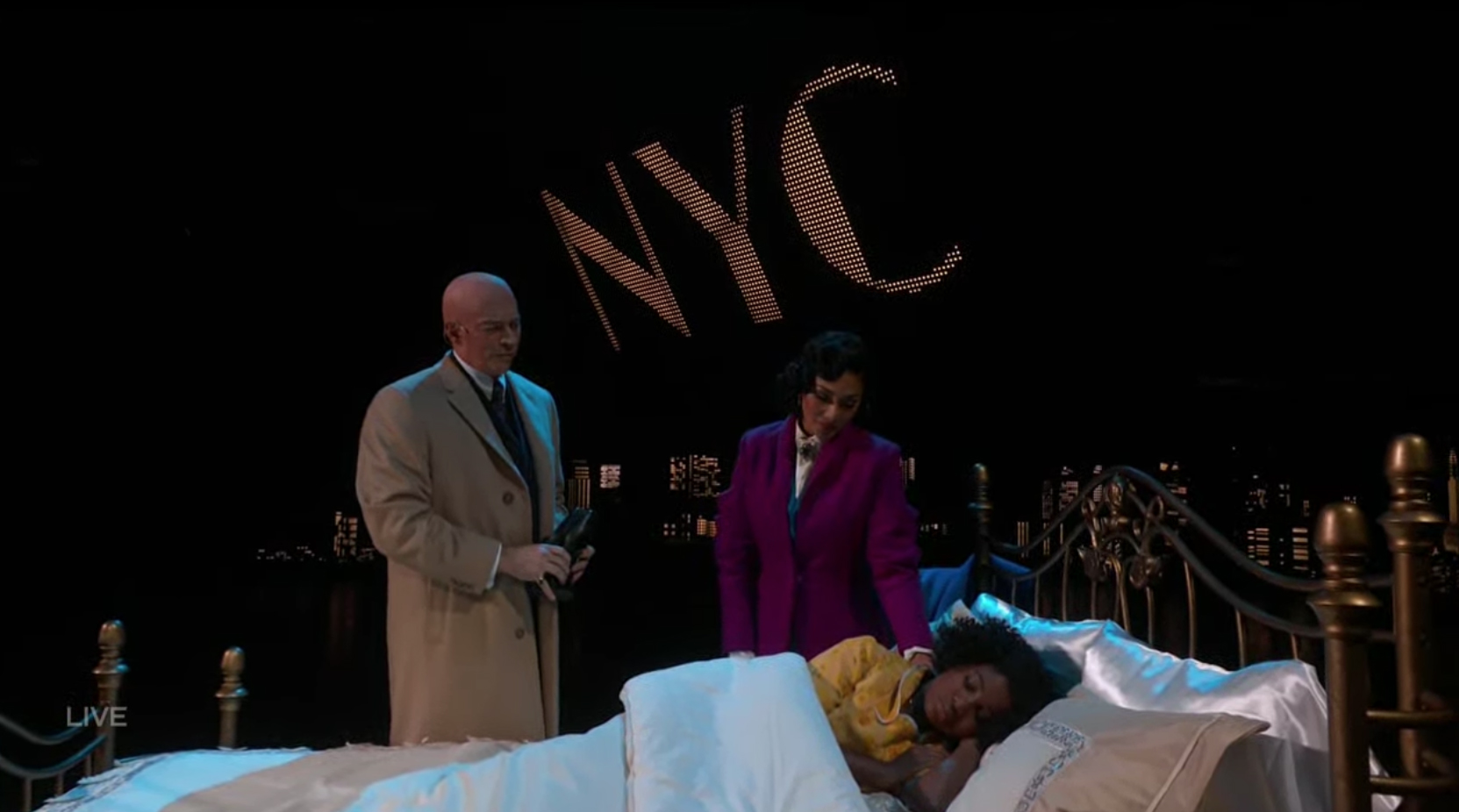

A particular strong number from a production standpoint was “NYC,” a number that didn’t appear in the film version that many Americans are familiar with.

This wide ranging scene included multiple mobile set pieces and additional scenic signage elements brought in to depict various locations around the city and ends with Annie falling asleep in her home after a night out at a Broadway show.

Here, the cityscape behind was lit in a golden amber and was far enough back that it was slightly out of focus, creating a dreamy, elegant look.

Meanwhile, the illuminated “NYC” letters that appeared earlier in the song faded in.

Things got a bit better for the show as time went on from a camera perspective, though there were still some scenes with rather dim lighting.

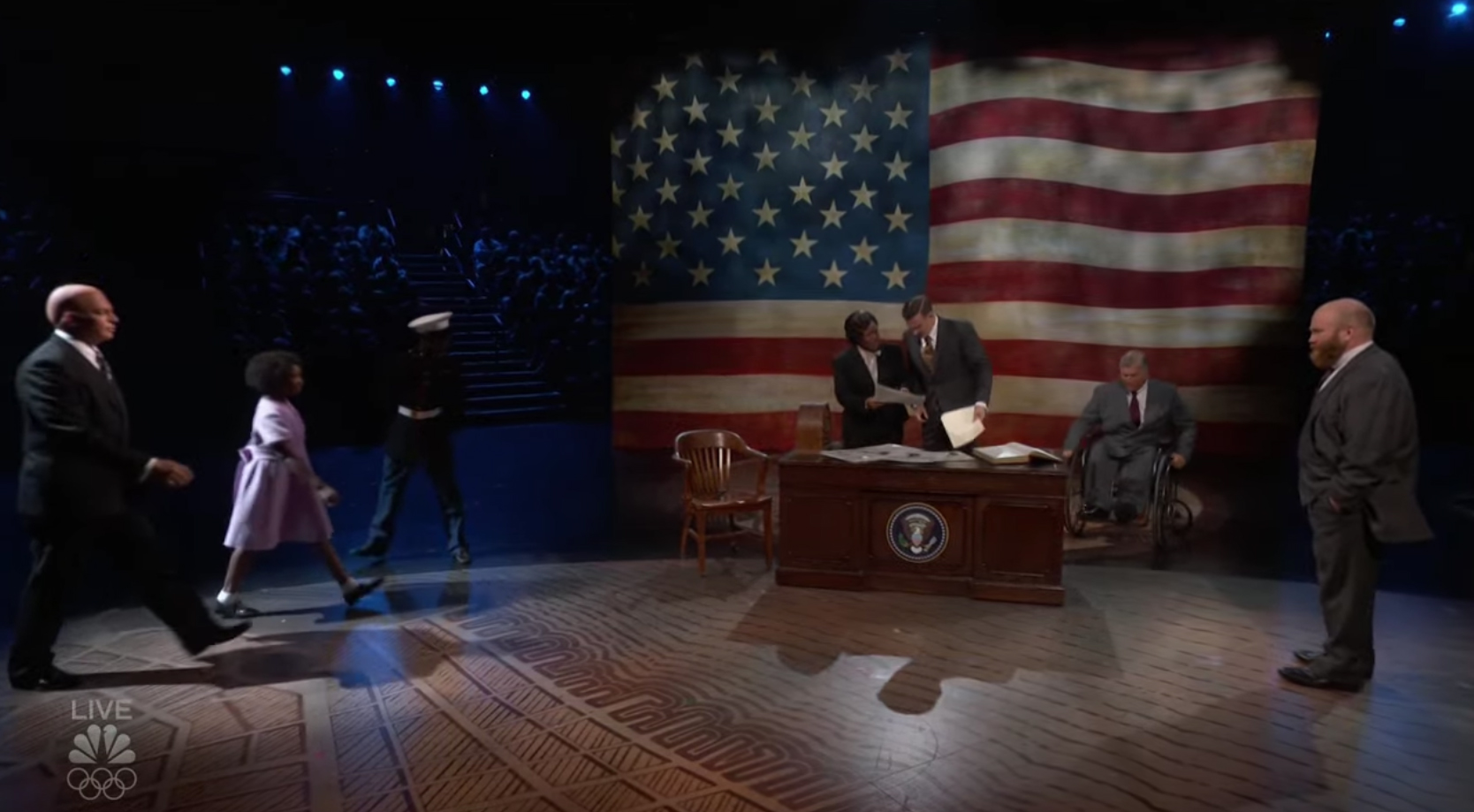

In a scene where Annie and Warbucks visit President Franklin D. Roosevelt was set in front of a weathered American flag background that matched the look of the rest of the production but was also decidedly less dramatic and flatter than some of the other scenic designs in the show.

Of course, the scene was very brief and Annie’s choreography called for her to stand on the president’s desk (because what’s a Broadway number without someone standing on a table — even if it’s the president’s desk?) so the full height of the flag got some good camera time.

The desk FDR sat behind appeared to be an attempt to create an amalgamation of the six desks that have been used in the Oval Office over time (assuming that’s where the scene was meant to be set), but it’s worth noting FDR’s desk for the entire time he was in office was open in the middle and wasn’t fronted with the presidential seal.

NBC also played homage to its origins as a radio network throughout the show, including in a news bulletin scene just before the visit to the president as well as with sponsor tie-ins, including a Wendy’s commercial. Vintage NBC style microphones and signage showed up on camera throughout the broadcast.

The production featured numerous tie-in commercials that often made use of songs from “Annie,” including spots from Walmart and Fisher Price.

The Fisher Price ad attempted to channel Jimmy Fallon’s “Classroom Instruments” segments by showcasing an “orchestra” playing a number from the show. However, a disclaimer on screen noted the audio had been enhanced, presumably because toy instruments can’t produce quite that rich of a sound.

“Annie Live!” appears to be garnering praise for its performance and feel good approach and, at the end of the night, part of the gimmick behind a live production is that things might go wrong and that audiences are experiencing something akin to live theater.

“Annie” may have benefited from some extra tech and rehearsing as well as screen tests for some of the lighting decisions (assuming they weren’t slip ups), but the creative team still deserves praise for creating such a large scale production space.

Photos by Eric Liebowitz and Virginia Sherwood and courtesy of NBC.

Correction: An earlier version of this story misidentified the location of the production facility.

Subscribe to NCS for the latest news, project case studies and product announcements in broadcast technology, creative design and engineering delivered to your inbox.

tags

NBC

categories

Broadcast Design, Broadcast Industry News, Featured, Live Event Set Design, Set Design