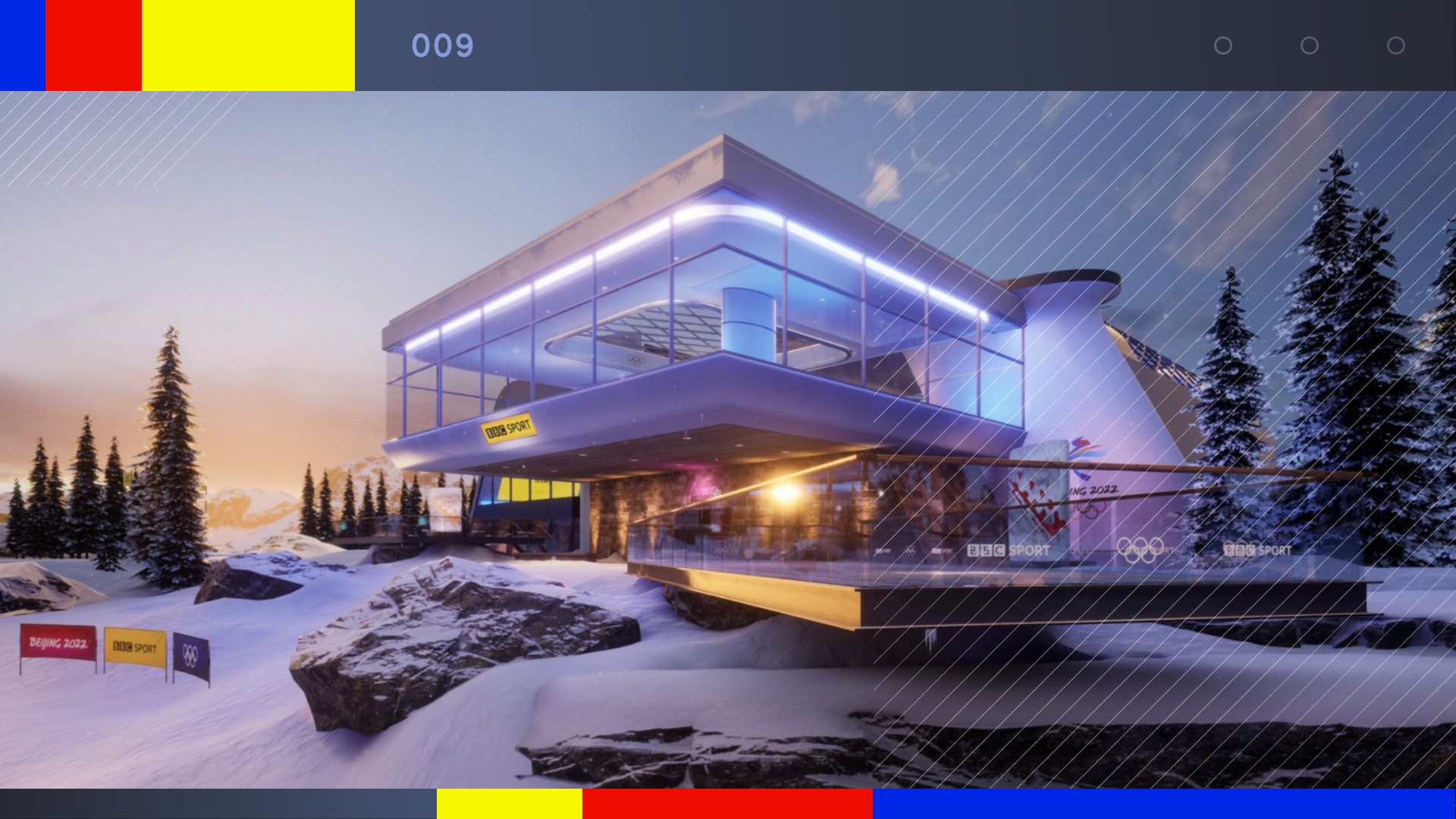

Broadcast Exchange: Creating a dynamic virtual environment for BBC Olympics coverage

Subscribe to NCS for the latest news, project case studies and product announcements in broadcast technology, creative design and engineering delivered to your inbox.

BBC’s coverage of the Winter Olympics in Beijing utilized the latest in virtual studio technology to transport presenters and viewers to a snowy ski resort.

Using the Unreal Engine paired with the latest technology from Vizrt, the project’s designers digitally sculpted mountains for the broadcast environment while carefully thinking through how to keep the visuals dynamic with data and highlights.

Jim Mann of Lightwell and Toby Kalitowski of BK Design Projects join the Broadcast Exchange to take us inside the virtual set design, the development in Epic Game’s Unreal Engine and the larger impact of the technology on the future of storytelling.

Listen here or on your favorite platform below.

Listen and Subscribe

Video: YouTube

Audio: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | TuneIn | Pocket Casts | Amazon Music

Show Links

- Gallery: BBC Sport virtual studio

- Gallery: BBC 2022 Beijing Winter Olympics studio

- Gallery: BBC 2020 Tokyo Olympics studio

Transcript

The below transcript appears in an unedited format.

Dak: Welcome to the Broadcast Exchange from NewscastStudio. I’m your host Dak Dillon. On the Exchange, we talk with those leading the future of broadcast design, technology, and content. Today, I’m joined by Jim Mann of Lightwell and Toby Kalitowski of BK Design Projects. The team recently completed BBC’s virtual environment for the Winter Olympics in Beijing. Using the Unreal Engine paired with Vizrt to create a dynamic studio, and even building some mountains in the process.

Dak: Thanks for joining me today to talk about the BBC’s unique presentation of the Olympics. You’ve learned a lot since you created the Tokyo studios, which also relied on this heavily virtual production pipeline. Walk us through those lessons, and then how that’s set up where we are today, with Beijing.

Jim Mann: Lessons. Yeah, it’s a funny one because it’s not just lessons, I guess, from Tokyo. I think it’s also lessons from Pres 2, which is the in-house studio that we worked on for the BBC, which launched a few months prior to Tokyo. In essence, the Winter Olympics studio, it’s that studio.

Jim Mann: It’s from the same green-screen studio, and it’s a modified version of that virtual set. Whereas previously we were using, or the BBC have been using, a main presenting space with windows, and then beyond the windows, it’s a photographic environment.

Jim Mann: Having seen the potential of what could be done on Tokyo, well, we thought, “Well, why not? You know, let’s go for it. Let’s have a bit of fun with this one,” and decided to try out the landscape in [inaudible 00:01:46], in Unreal. We started looking at this… it was actually before Tokyo, wasn’t it?

Toby Kalitowski: Yeah.

Jim Mann: Am I right, Toby?

Toby Kalitowski: March, it was March. March or April last year. I think the biggest thing in terms of lessons learned from Tokyo was the multi-level approach, where you’re offering the editorial team various different positions they can use for different program strands.

Toby Kalitowski: That was fantastic in Tokyo. Everyone loved that, and that sense of directors being able to explore and find new spaces to create their programs. That’s kind of what was at the core of this idea of creating multiple levels and different presentation spaces outside, as well as inside.

Jim Mann: I’m a huge fan of serendipity. I think there’s a lot of that in there, but I also like to think that serendipity is only going to happen if you’ve got some decent design ideas, and a decent context in terms of the design to start with. It’s about just extending on what we’ve done before.

Jim Mann: It’s a team we’ve worked with previously on quite a few jobs now, and we’ve got to know them quite well. So, we tend to know what they like, and we tend to know what they don’t like. I think that helps as a designer, when you’ve got a better idea of what will appeal to the client, and what the client can make use of.

Jim Mann: I think what’s really happened with the Beijing Winter Olympics studio is that the BBC’s taken ownership of it. They’re doing things that we thought would be good, but they’re taking it just that stage further.

Jim Mann: I guess one good example of that is, there’s a seating position where, when we were putting together packs of presentation images for the designers, in its initial stages, we were spinning around the Unreal model. We had a look back at the building from within the landscape, and immediately, it’s like, “Yeah, this is interesting. Can we make use of this?”

Jim Mann: So, of course being a design presentation, we dropped in a 3D figure, set up a fairly standard mid-shot with the building in the background out of focus, but getting that sense of a presenter in the landscape, and thinking, “Oh, this will be sort of top of the show. You know, they’ll do a quick announcement there, then move inside.”

Jim Mann: That then developed, you can tell they were interested because they then said, “Oh, well, can we have a floor?” Because the presenter was floating in the sky. So, yeah, we built a little hill for them to stand on. Of course, if it’s just snow, that’s not very interesting. So, you put some rocks in there just to break up the landscape.

Jim Mann: The next thing you know is, you’re being asked if they can sit on the rocks. So, you put in a rock that they can sit on, and then it’s, “Well, could there be a bench?” We had a little bar area, so we pulled a bench across. The next thing we know, they’re borrowing stools from elsewhere in the BBC, covering them with leftover bits of green screen.

Jim Mann: Hey Presto, there’s a brand-new presentation space called “the bench”. It’s an informal space and it just works, but it’s working because we’ve done all the hard work in the landscape and the rest of the design. I think those kind of things have been what’s really rewarding about this particular project.

Dak: Now, you mentioned Studio Pres 2. For those who are not familiar with that space, just give us a quick overview of that piece of the project that led up to this kind of design iconography that you all have settled on.

Toby Kalitowski: It was a kind of lost studio, and it was never really used. They wanted to create a green screen, generic environment, and we created a multi-level environment for them. The idea was, at the outset, that this would be something that there would be areas that we would never even think about using, possibly, in the next year or the year after.

Toby Kalitowski: It would be a constantly evolving scenario. That was embraced hugely by the BBC. It’s been very successful. It’s been massively overbooked, so much so that it’s difficult to get into the studio to do testing, and all the rest of it. So it’s slightly… we’ve been a victim of our own success in that respect. It’s been quite hard to get time to test new environments in there, but that formed the basis of this new studio.

Dak: Taking what you learned from Pres 2, you have these sleek white columns, you have this embedded fireplace, you have these sweeping panoramic mountain scenes. Walk us through the design for the Olympics.

Toby Kalitowski: The architecture was there. As you say, sleek, modern environment was there. We needed to create something that had warmth, so we added the fireplace and things like that. There were certain things we had to do within the actual set. Like, we added ice to the sunken floor areas.

Toby Kalitowski: The main thrust of the whole project, really, was the landscape. That’s where we had an amazing time. Unreal was fantastic, and Jim was amazing, and we learned so much. Yeah, creating that 3D environment, a giant map was really the thrust of the whole thing. Then, placing our presentation decks out actually in the snow as part of that.

Toby Kalitowski: We discussed things like, should they be wearing quilted jackets, and how far… I think what’s interesting about the whole thing is, you’ve got to take it with a pinch of salt because we’re not yet in the world of photorealism.

Toby Kalitowski: It’s almost… We have people in Tokyo who thought we were in Tokyo. We never thought that would be the case. I have had people say to me, “Are they out in Beijing?” I’m like, “Have you actually seen Beijing?” It doesn’t look anything like this lovely, alpine, snowy background.

Toby Kalitowski: So it was an exploration, the idea of using Unreal to create a landscape. It was a bit of a punt on our part, in that there was no guarantee of any work. It was a, “Hey guys, what do you think,” to this. It’s probably fair to say that there’s probably a bit of our inner [inaudible 00:08:30] coming into it, in that it’s almost like a Bond baddie embedded in the mountain scape.

Toby Kalitowski: It was having a sense of fun and having a play, a “what if”. “What if we did this, what if we tried that? Wouldn’t it be cool if we did this?” I think that’s where a tool like Unreal is fantastic, because we were able to just develop that and play with that, and really have a lot of fun with that kind of idea.

Toby Kalitowski: At the end of the day, there’s ski tracks in front of the building, all the paraphernalia that you might find around a ski resort, but at the end of the day it was, “Let’s have fun with this.” That’s one of the nice things about working with sport, TV sport, is that it can be quite playful.

Dak: You’ve mentioned Unreal many times. This is, I believe you’ve told me before, one of your first big projects where you’ve done most of the design and development straight in Unreal, and not necessarily in Cinema 4D or another piece of software first. How did that change your workflows, and just the way you even thought about conceptualizing these spaces?

Jim Mann: Massively, massively, because take Tokyo. Tokyo started out, it was, Toby would build a model, turn it to me, I’d do something, send it back to him. It was like this game of tennis, with models going backwards and forwards [inaudible 00:10:02] packages, which it’s not ideal. It was just swapping ideas like that.

Jim Mann: Then, our pitch presentation was rendered in V-Ray, and we did an animation for that. Of course, that meant making sure that certain parts of the model were finished so many days in advance, and that spare machines were churning away for a few days, just to render out all the frames of the animation.

Jim Mann: With this Olympics, because we just thought, “Yeah, whatever, let’s just go for it.” We’ve got the main space already, or we’ve got the shell already in Unreal. So, we just started adding to it in there, in Unreal, taking bits into Unreal. Because we have that power to move around and see things, it was about exploring, about finding out what worked. I think that helped. It helped, as we took out quite a few things, but we also saw opportunities and potential.

Jim Mann: We were able to bring that in, and not just bring it in as a suggestion, but bring it in as something more credible, something more viable. When you’d think, “Well, what if we had some decking?” So, you add some decking, and then you add a snow particle system, and all those things start coming together. It’s like the picture really starts to evolve.

Jim Mann: It’s really fluid. You’re not spending your time waiting for a render to finish, which is the most depressing thing ever now. If we had a presentation, we’d then, in a fairly short space of time, put together a short animated sequence. Being television, that showing the client something, as a volume in which a camera can move, that’s gold. That really is gold.

Toby Kalitowski: Typically, certainly towards the latter stages of developing the design, we would spend the best part of a day, or like a whole afternoon, on Zoom. We would be in the Unreal model. Jim would be moving around, and it’s just incredible. Jim would be painting snow and we’d be saying, “Okay, let’s lift the mountain here and, okay, let’s paint some trees.”

Toby Kalitowski: Obviously, there were lots and lessons to learn about resolution of things, paring stuff back, and optimization, but actually, the process of designing, it’s so incredibly fluid. Just the idea of stepping back to where we were, like Jim said, even a year ago, just feels inconceivable. The idea of waiting for something to render is just madness. So, it’s been really exciting, really thrilling, I think.

Dak: Then, the final product was integrated with Vizrt, the Viz Engine 4, and a variety of their other tool sets. Talk about that process, and making it all sync.

Jim Mann: The great thing about working with a client like the BBC is, they’ve been using Viz for forever, and there’s a good knowledge base within the BBC. It’s a really good team of people working in the graphics department at the BBC.

Jim Mann: Our main point of contact there was a guy called Andy, Andy Bowker. In a similar way to myself and Toby passing models backwards and forward at the beginning of the process, towards the end, it’s myself and Andy passing copies of the Unreal project backwards and forwards, and then making adjustments.

Jim Mann: I think what’s been really good this time is, Andy’s also been involved in the Pres 2 work. So, Andy understands not only that studio, but he understands this project, and he understands this design as well. So, he’s been able to suggest things along the way.

Jim Mann: The penguins, the deer, and the polar bear are all down to Andy. He’s been able to take on that whole process of taking the Unreal project and doing the integration with Viz. He also takes on a responsibility beyond that, in interacting with the virtual set operators, who work in the gallery at broadcast time.

Dak: The studio has a lot of virtual screens in it as well, so that way, they can bring in highlights or queue up graphics. Talk about the challenges of integrating those into a virtual space, and making sure the presenters or the talent can fully utilize and understand, even, what they’re looking at.

Toby Kalitowski: For Pres 2, we had designed into this scenario, a projector, which projects an image onto the green [psych 00:14:55]. So, we have a standing position which essentially is used for all the setups in the Winter Olympics. It’s a very, very small area of the set, to one side of the studio, where we have two standing presentation positions.

Toby Kalitowski: In between them, we have our projection zone. So, really, that then defines your position of all the screens within the virtual space. Obviously, sometimes we didn’t do that. In which case you need to have a floor monitor giving you an eye line.

Toby Kalitowski: Actual design of the screens, you wanted to make the screens feel as believable as possible. So, we actually ended up making screens quite chunky, rather than incredibly thin, bezel, lightweight screens that you can have. We just felt they were too flimsy to feel like they were believable as an outdoor screen. So, we spent a bit of time working on the development of the actual virtual assets for those.

Jim Mann: It’s almost as if things have to look not as good as they could be. You almost have to degrade the designs slightly in order to achieve a greater sense of credibility and believability. There’s also areas where we’ve got the BBC logo on the floor, but we’ve scuffed it, and scratched it, and damaged it, and just made it look like people have been walking over it for a week or two.

Jim Mann: If you’ve seen that video of Aimee Fuller practicing her snowboard in the studio, you could probably understand how that might get damaged like that. It all adds to that sense of, I guess, it’s care-worn.

Toby Kalitowski: We had lots of conversations about exactly that thing, about believability, and that fine balance, the uncanny valley thing, the closer you get, the more weird things can be. It’s quite a hard area to make sure you are in a sweet spot.

Dak: I think you just answered what I was going to ask. Obviously, when it comes to virtual studios now, we are seeing two approaches. The completely abstract, and then those that are much more grounded in reality. The ones that often fail are those weird ones that are somewhere in the middle, where it’s like, “Oh, these are the correct-size mullions on a window,” but then suddenly the ceiling is 300 feet tall.

Dak: This space, what I like about it is, it feels absolutely like a real ski lodge. It feels like something that you could find at the top of a gondola in Canada. So, it feels very believable, when some of the other studios out there, just like you mentioned, the uncanny valley effect, are they a spaceship? Where are they exactly? What’s that sense of place beyond just the snow behind them?

Jim Mann: If a viewer is looking at something and trying to think, trying to decide, “What is it? What’s it meant to be,” then on a certain level, we’ve failed. Whereas I think with the Olympic studio, I don’t think… there’s no guessing. There might be a sense of, “Where are they?” Which is very different to, “What is it?”

Jim Mann: The “Where are they” is a much more interesting conundrum to have. There is an element of that. I suspect that probably comes… my background is I’m a registered architect. Architecture wasn’t very interesting, I moved onto different things, which I’m so much more engaged in, but I’ve still got that sense of, I know how big a mullion is. I know how high a ceiling would be.

Jim Mann: If you’ve got a ceiling any higher than that, well then, where’re you getting that glass from? You can’t get glass panels… and there’s all those limiters in my subconscious. We can’t do anything too ridiculous. It’s almost like we’re saying to ourself, “Well, how would it be built? You know, what would it be made of? What would the detailing be? What would the joints be?”

Toby Kalitowski: Every element that we deal with it is true-to-life scale, so every step, every handrail, every beam, is justified. If it’s a cantilever, it has to be thicker than… it has to do its job. I think you’re right. There are lots of sets out there which have a theatricality to them, and they don’t tie themselves to those structural rules, really.

Toby Kalitowski: They may look great, but there’s something about it where you just think, “I can’t invest in it. I can’t believe in it,” and the person standing in it doesn’t feel like they’re a part of that scene. Yeah, all of our reference, all of our excitement, really comes from architecture. It’s an amazing place at the moment, to be able to play, in such an environmental way, creating spaces that are more like buildings than they are like sets.

Toby Kalitowski: I don’t feel, really, we’re set-designing anymore. I think we’re designing environments, but it is interesting how out there, people still are doing… there’s fourth-wall, quite stagey-feeling virtual sets where you just think, it’s almost like a proscenium approach to theatricality. Which is bizarre, because we can do anything, and yet we’re stuck in a Victorian theater sometimes.

Dak: For it to work really well, it has to be really spot on with all the details, or it has to be completely abstract, where then you just have a bunch of floating glass in an abstract space. Because, then, you know it’s fake and you don’t conceptualize that in your brain as being real, but even in Beijing, even the snow is fake for this Olympics.

Dak: So, everything is a little bit man-made. In terms of virtual production and what you all are doing, what challenges are still out there that really need to be solved to make your workflows better, to make the models better, just for any of it?

Jim Mann: Ooh, I think possibly performance issues. Obviously, creating a virtual environment as opposed to a virtual set, it’s much more expansive. Unreal is great at handling those large data sets, but I’m still getting used to the idea that you can’t populate every single part that you see for every shot, with the highest level of detail.

Toby Kalitowski: For me, it’s all about lighting, the quality of lighting, and the quality of contact of the presenter within the virtual space. I just want to see fantastic contact shadows, fantastic reflections. That’s limiting for us, specifically. I know Viz are developing that, and that’s obviously just around the corner, so there’s lots just around the corner, but the closer you get, the further you feel you are, in a way.

Jim Mann: The contact shadows and contact reflections, it’s coming in now. I think it may have been possible to do more with that at the Olympics, but this comes back to the issues with the popularity of the Pres 2 studio, in that it was so busy, and before the Olympics, it was busy with the Australian Open tennis.

Jim Mann: So, there wasn’t any opportunity for the guys at the BBC to actually test those features properly, to get them working properly. It’s integrating the presenter with the virtual set. A lot of that comes through… it’s either shadows or it’s reflections. If you’ve got a real floor, that’s great, but a real floor can be limiting.

Jim Mann: You have to trade off the flexibility of, are they on ice, are they on wood, are they on snow? Those are the three different virtual floors we’ve got at the moment. If we had just one floor material, that’s a magic carpet that’s traveling around this virtual world, which they are constantly stood on.

Toby Kalitowski: A thing, for me, that would be really interesting to explore more, is to have full control of the lighting within the virtual space, from the gallery, so we can work more closely with the lighting director. I’ve had tantalizing experiences of the possibilities of doing that, but haven’t fully embraced that yet.

Toby Kalitowski: That feels like a no-brainer, that has to be the way, you have to have a full control of virtual and physical lighting. Of course, that’s money. Ideally, you want moving lights, you can adjust all the color temperatures on the fly, and it’s all preset. Of course, people are doing that, but you need the budget to do that.

Jim Mann: Everything’s making a demand on that graphics card, and it all starts and finishes at the graphics card. As graphics cards get bigger, the software and the designers, we’re trying stuff more through the graphics card. So, we’re always going to need more.

Jim Mann: I’ve been doing this now since, blimey, I think my first 3D with a render was 1995, an AccuRender with Pentium 120s with like 128, not gigabyte, megabytes of RAM.

Jim Mann: You were always trying to cut the polygons down, and cut the lights down, and wait a few hours for a pretty awful, but at the time felt fantastic, [inaudible 00:24:22] render. It feels a lot like that again, but so many generations on, and it’s exciting. It really is exciting.

Dak: In terms of the R&D, you’ve talked a lot about just that process. Is it a process that is longer than a traditional scenic load-in and training, or is it something that it’s still going to be a little quicker, just getting the set up and running on the virtual side?

Jim Mann: I think when the hardware’s there, when the studio setup’s there, it’s probably pretty quick. We could probably turn something round and get it loaded in fairly short order now. As to how many day that would be, I don’t know, but everything depends on the complexity.

Jim Mann: If you’ve already thought about it properly, you already understand the limits of the physical space, and how that physical space relates to the virtual set, and vice versa.

Jim Mann: So, you already know where you expect your talent to be within that design. You already know where you expect the cameras to be, and where the cameras can’t go. This should get more fluent and faster, but again, as things get more complex, then we’ll want to do more complex things. So, [inaudible 00:25:39] again.

Toby Kalitowski: It’s a conversation we had with John Murphy, who’s head of graphics, creative head of graphics at BBC, and we were laughing and saying, “I think people… the general assumption is, if it’s green screen, it’s kind of easy, because there’s nothing there and you’ve just got to plug it in and play.”

Toby Kalitowski: But actually, in terms of time and cost, currently, as it stands, it’s more expensive than a comparable physical set install, in terms of the time setting it all up. It’s very difficult, because you can’t compare it anymore. Because obviously, we can’t build what we are building, physically. It’s not like we could even attempt to do it.

Toby Kalitowski: So, the physical elements become way simpler, and all of your time and budget is going on the virtual side of stuff. I think it’s generally costing more, I would say, at the moment, but that’s because there’s so much of ironing out of issues. But I think every production’s having that. I don’t think anyone has it easy.

Toby Kalitowski: I don’t think anyone’s cracked it, and they’re just breezing through stuff. I think everyone is having to deal with the latest versions, and graphics cards, and “Oh, there’s an issue with the [inaudible 00:26:54] box and the swop out, and do that.” Do you know what I mean? It’s constant stuff that’s happening.

Dak: To wrap up, what’s next for what you all are working on?

Toby Kalitowski: We’re currently working on a pitch for the Commonwealth games, which takes place in Birmingham this summer. I’m doing a lot of work at Bloomberg in the UK, who are expanding their studio facilities here.

Jim Mann: I’m currently working my way through every regional studio for ABC Australia. So, yeah, it’s February in England, the weather’s miserable. I have to spend my day looking at photographs of beautiful sunsets in Hobart or Tasmania. Yeah, it’s just to make me feel worse. If any broadcasters out there would like a studio designed for the World Cup, we’re ready.

Dak: They say the world of sports never stops. There’s always that next event. I’m sure soon you’ll have to start thinking about another Olympiad only two short years away. Thanks for listening to the Broadcast Exchange. Make sure to subscribe for the latest Broadcast Exchange episodes on your favorite podcast platform, or watch our video episodes on YouTube.

Subscribe to NCS for the latest news, project case studies and product announcements in broadcast technology, creative design and engineering delivered to your inbox.

tags

2022 Winter Olympics, BBC, BBC Olympics, BBC Sport, BK Design Projects, Epic Games Unreal Engine, jim mann, lightwell, Olympics, sports set design, Toby Kalitowski, virtual set design, Virtual Sets, virtual studio, virtual studios, Vizrt, winter olympics

categories

Augmented Reality, Virtual Production and Virtual Sets, Broadcast Exchange, Set Design, Sports Broadcasting & Production, Virtual Sets