After congressman confuses video wall for real room, what standards should be considered for these backdrops?

Subscribe to NCS for the latest news, project case studies and product announcements in broadcast technology, creative design and engineering delivered to your inbox.

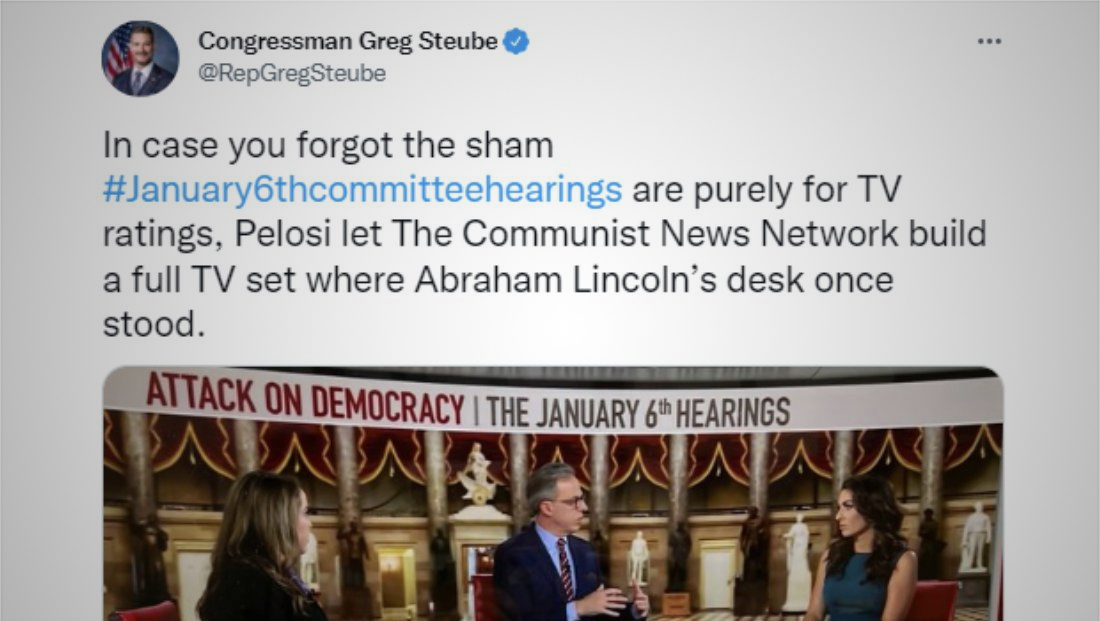

A Florida Republican congressman has been called out after a now-deleted tweet appeared to accuse Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi of allowing CNN to “build” a set inside of the U.S. Capitol.

Rep. Greg Steube tweeted June 16, 2022, that “Pelosi let The Communist News Network build a full TV set where Abraham Lincoln’s desk once stood” while also calling the January 6 insurrection hearings a “sham.”

The reference to “Communist News Network” is a moniker used by Republicans and right-wing media as a way to refer to CNN, whose name originally stood for “Cable News Network.”

Steube’s reference to “a full TV set” appears to be using the word “set” in reference to scenery as opposed to an electronic device that displays video pictures.

Rep. Greg Steube removed his tweet calling CNN "The Communist News Network" who built "a full TV set where Abraham Lincoln's desk once stood" because was informed this what we the TV business refer to as a screen. pic.twitter.com/h7HLPEOFCa

— andrew kaczynski (@KFILE) June 16, 2022

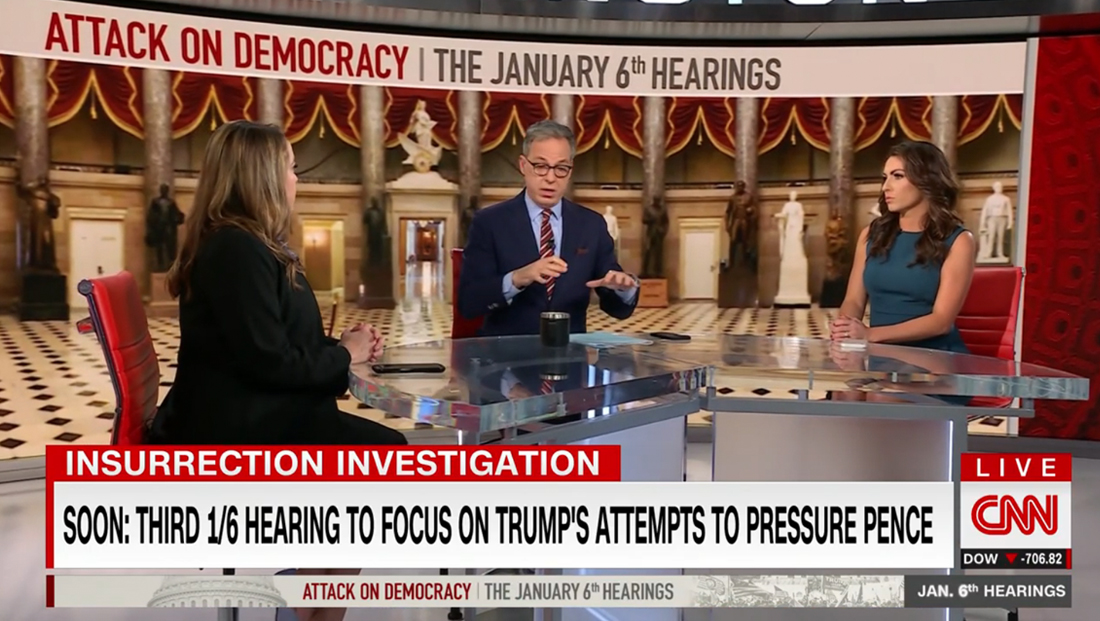

The tweet was live for about 30 minutes before someone apparently got wise to the fact that CNN’s Jake Tapper was actually sitting in an enclosed TV studio with an image of National Statuary Hall, a historic room inside the Capitol, shown on the LED video wall behind him.

CNN, like numerous other networks and local news outlets, has become a big user of seamless LED tiles that can be combined to create giant screens that stretch from the floor to ceiling and are often 20-plus feet wide.

These panels, when connected to a video source or control room, can then be used to show any video or still image.

That’s what was happening June 16 — Tapper and his in-studio guests were seated in front of a large LED array inside the network’s Washington, D.C. bureau which, while close to the Capitol, is definitely not inside of it.

Before the advent of LED panels and rear projection, TV studios frequently would depict a variety of imagery behind anchors printed on thin, translucent film stock with lighting behind it, creating what is known as a duratran.

When viewed quickly, it’s perhaps understandable that one might make the mistake of thinking CNN had built a set inside of the Capitol.

However, it doesn’t take much analysis to realize there are a few things “off” about the look.

This screenshot illustrates more clearly what the scene Steube tweeted claiming that CNN had built a studio inside the Capitol looked like on air.

First, the photo appears to have had a series of effects or filters applied to it that give it the feel of a video game scene as opposed to real-life — which could have been a purposeful choice made by CNN.

The image also reads a bit flat, without the sense of depth one might expect from it being inside the actual room.

In addition, even an empty room will often still have subtle motion — such as a fluttering curtain or shifts in light on the floor — that CNN’s view was lacking.

The perspective and scale is also off — had CNN genuinely built a studio inside of the hall, it’s not likely that as much of the black and white tiled floor would be visible behind the actual floor the anchor desk is sitting on, which is visible in the shot Steube tweeted. The angle of the floor is also a bit more extreme than might be expected.

In addition, Statuary Hall, while not small by any means, likely appears to be larger than it actually is should one assume the graphic on CNN’s video wall was the real, actual view from a platform built inside of the room as opposed to a backdrop.

Another hint is the fact that the large banner running across the top of the background reading “Attack on Democracy: The January 6th Hearings” appears flush against the view of the room no matter what camera angle is used — and also remains so even when the camera moves on air.

In reality, if this banner was some sort of structural element installed above the anchors, the view of the room would shift in comparison to when shot from different angles or as the camera wanders around in wide shots. Even if CNN was permitted to mount a giant banner along the walls of the room, it too would change perspective depending on camera angles.

Perhaps less obvious to the average viewer is the fact that, in many wide shots, CNN also showed a simulated red panel and metal bevel on at least one side of the background. These too, would not remain fixed to the view of the room if it was actually some kind of graphical panel and metal frame mounted behind the anchors in the room.

Video wall backgrounds and ethics

All that said, the incident does bring attention to a larger issue that broadcasters have wrangled with over the years — is it misleading to depict anchors and other talent sitting in front of views that aren’t real?

As video wall technology has become more prevalent and improved in quality, the question of what viewers perceive becomes perhaps more important.

To understand this issue, it’s important to realize the difference between a background meant for scenic purposes and one meant to represent the actual location of someone.

In the case of the former, the background is just that — a background. In other words, while it may be used to enhance storytelling, it is still meant to be read as a scenic or visual element before serving as a representation of location.

For years before LED video panels were even invented, news anchors have been sitting in front of backgrounds that are not real.

Some of these were straightforward — such as a sweeping panoramic cityscape based on an actual photo. Many studios that used this approach would have multiple duratrans installed that could be switched out depending on the time of day a newscast aired, typically with at least a daytime and nighttime view.

Anchors at KDFW in Dallas celebrate a new duratrans on their set in 2021. This design uses 3D ‘Fox 4’ elements from the station’s graphics package, creating the look of a wallpaper of sorts.

Others took the role of background more literally and featured elements that could only be read as scenery — such as station logos or swaths of color often matched to graphics packages.

Of course, duras had one big shortcoming that made them less realistic — they couldn’t display the movement of objects printed on them.

Some duratrans installations would add the suggestion of movement by adding flickering or other lighting effects, but, for example, cars on the background wouldn’t be able to move along streets or over bridges.

The background also couldn’t adjust for every weather condition or shifts in daylight as seasons went by, so they often were meant more as an idealized view of the city.

However, it was not uncommon for viewers to think that the station actually had a “window” that provided the view being shown. Stations would occasionally get calls asking why it wasn’t raining behind the anchors when it was in real life or have members of the public tour the station and be surprised that there wasn’t an actual window in the studio.

Some studios do actually have windows that are used as backgrounds, but this wasn’t nearly as common as duratrans and typically real windows can’t provide the type of sweeping views, often depicted as viewed from the outskirts of the city or from high atop a nearby elevation, that these printed backgrounds often portrayed.

For that to be physically possible, the station’s studio would have to be located in a place that naturally afforded that view, meaning, in many cases, this would require the building to be far away from the city or atop a harder-to-reach landform. While stations are often located outside of the downtown area they serve, they tend to stick relatively close to the area so that it is still easy to get to the city for news coverage, assuming the newsroom and fleet of vehicles are at the same facility.

Even in the fairly rare case of studios being located in a different facility than from the newsroom, the studio would still need to be relatively close to the station if staff need to travel between both locations.

Other duratrans would depict “still life” versions of newsrooms and control rooms — sometimes rendered from 3D models. In many cases, these images were completely imaginary and not based on any real space.

In this 1996 screenshot from a video, former NBC anchor Brian Williams is shown sitting in front of a printed background depicting the view of a sprawling fictional newsroom that was a primary background for ‘NBC Nightly News’ for years. While the desk where Willliams’ papers is real, everything behind him is a glorified oversized poster.

Again, because they were printed pictures, they couldn’t show real action such as monitors flickering or people walking around (or even capture the subtle movements of someone working at a desk), so they were often depicted, somewhat ironically for a look that was meant to provide a peak into the newsgathering process, as empty spaces.

Some duratrans would use light effects to make it appear that monitors were flickering. Later, some even included a real monitor embedded in the midst of the printed background, often positioned to make it appear it was part of the background scene.

The green part of this SportsNet studio is a more advanced implementation of chroma key, but the principle remains the same.

Newscasts have also used chroma key technology to insert backgrounds behind anchors. This meant anchors might be sitting in front of a solid, often garish blue or green wall in the studio. The station used equipment that would identify distinct hues in the video feed and replace them, in realtime, with another image.

These images, however, were often graphics meant to illustrate the story and changed frequently throughout the newscast and therefore were less likely to be confused as actual views of any locale and read more as visual representations.

Technology improves in-studio video panels

The rise of the rear projection cubes, and later larger RP screens, made it possible for anchors to start sitting in front of oversized images without the need for chroma key, though for years the cost of these units were out of reach for smaller stations.

As LED video panels become favored over rear projection and the cost came down, more and more news sets make use of them.

A non-seamless video wall at WAGA in Atlanta takes advantage of the panel’s lines to create distinct segments to the graphic on it.

A typically less expensive option is for stations to use LED panels that are not seamless but do feature a low-profile frame that results in what appear to be black lines running through the look, which was also similar to how rear projection cubes were used in arrays.

In general, these panels have a built-in advantage in terms of viewers mistaking whatever is being shown on them as not being physically there since the lines tend to make it more obvious that the background is, at the very least, a simulated view.

However, seamless panels have become more affordable and stations and networks tend to recognize the value in investing in them to help enhance storytelling and create eye-catching shots.

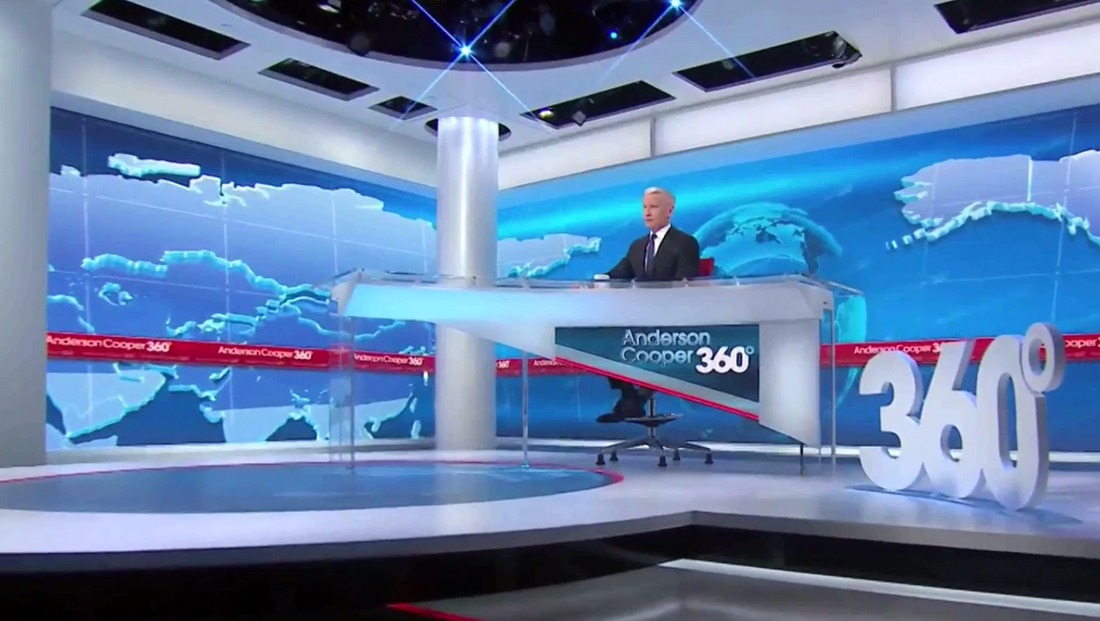

In this view of ‘Anderson Cooper 360‘ originating from the set in Studio 21L at CNN’s New York studios, all of the surfaces shown with the blue world map design and red band are seamless LED panels. The column, desk and wall and ceiling segments surrounding them are real.

It’s not uncommon for studios to be filled with LED video walls to the point where designers have to get creative to blend hard scenic elements with the large swaths of electronic canvases.

Another trend in the industry is using LED video walls or even single panels to show looped video clips or live feeds of locations behind talent. This allows there to be movement in the background, a big advantage over printed duratrans. Movement is often simplified, however, with people only shown in profile or silhouette. Some of these clips are captured during off-hours to reduce the amount of people in the room.

It’s become more common for newscasts to showcase a video loop or real-time view of a live camera behind anchors. Often these cameras are locked down shots from somewhere in the city — or a view from the station’s antenna tower affording sweeping views of the area.

The pandemic and video backgrounds

The COVID-19 pandemic made the use of video panels that suggested anchors were somewhere they weren’t even more commonplace.

For a period, many anchors were working from home and sitting in front of large TV screens that, as time went on and these setups became more sophisticated, be used to show video loops of real newsrooms, control rooms or other scenes as well as topical graphics.

For example, “Nightly” originated for months from inside anchor Lester Holt’s home with a video loop of the network’s fourth floor newsroom shown behind him even though he was not going to the building regularly.

Ethical questions

One of the key questions when determining ethical standards of backgrounds is whether or not using the background is germane to the coverage being provided.

For example, an anchor can still report the facts of the story without being physically seated in front of a newsroom. The newsroom is also not, at least in nearly all cases, the subject of the story.

In that sense, the view of a newsroom is being used as, quite literally, background to enhance the look of the newscast — but not overlapping into the story itself.

Similar reasoning could be used for cityscape backgrounds — it typically doesn’t matter if the anchors are, in fact, sitting in front of a real or simulated view of the city and the station isn’t attempting to convince viewers they are seeing a real-time view.

However, like with most things, context also matters.

An anchor somehow pointing to a duratrans as being an accurate depiction of the current weather would be considered misleading.

In the case of live camera feeds on video walls behind anchors, since what is being depicted on the screen is actually happening somewhere, it’s less of a conundrum assuming the talent does not purport to be on the scene.

Common sense?

In many cases, broadcasters also rely on viewers to have at least some basic reasoning and logic skills.

For example, they may rely on viewers to realize that a polished anchor without a jacket is not actually sitting out in the middle of that snowstorm (even from some kind of temporary shelter).

In fairness, CNN’s use of the Statuary Hall photo was a bit more subtle than that — which could have contributed to Steube’s error. In fact, his tweet speaks more to the rising emphasis on instant posts over accuracy since, had he taken some time to look at the image, it might have become more obvious CNN hadn’t set up shop in the room.

That said, there is a portion of the population that is inherently more tuned to visual hints such as the ones that existed in CNN’s background.

Often the question comes down to the “average” or “typical” viewer question and if that persona would be misled.

Making it clear a background is a background

Sometimes live feeds or other backgrounds will be purposefully altered to make it more obvious they are meant as background.

This could include adding elements over them to make it a bit more obvious that the image is not a depiction of an actual view. This can include inserting repeated text, still or animated, over it. Since text does not naturally float in midair, there is at least some assumption that what’s being shown is not the actual view.

In this image, ‘CBS Evening News’ anchor Norah O’Donnell is shown in front of a view of the Capitol Rotunda, a real place. However, the color effects and scale of the image make it fairly obvious that it’s not meant more as a background element than a real view.

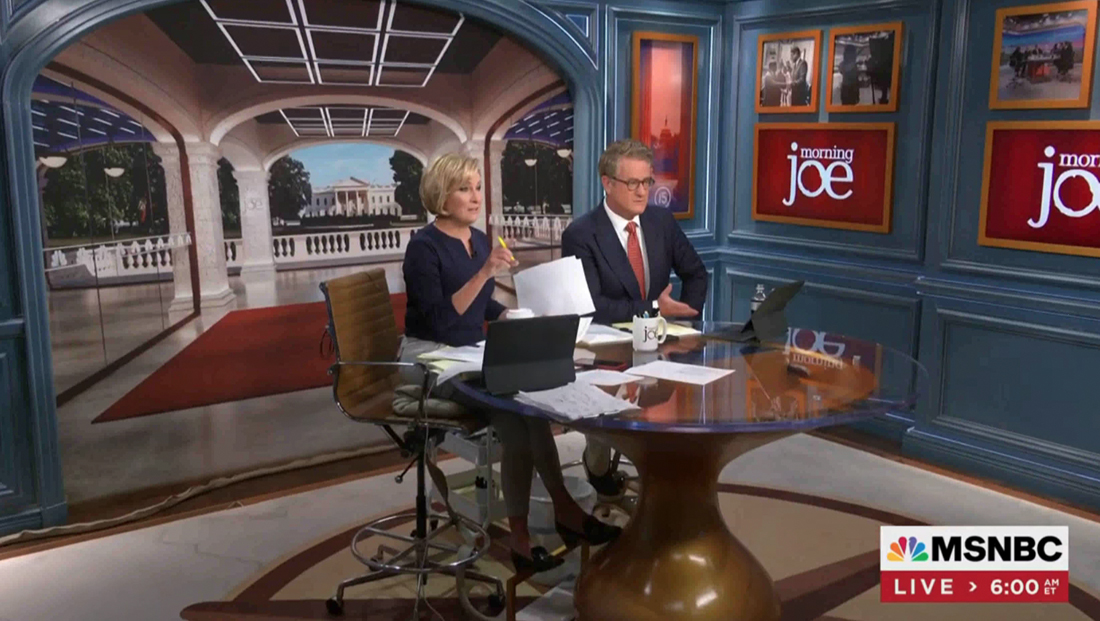

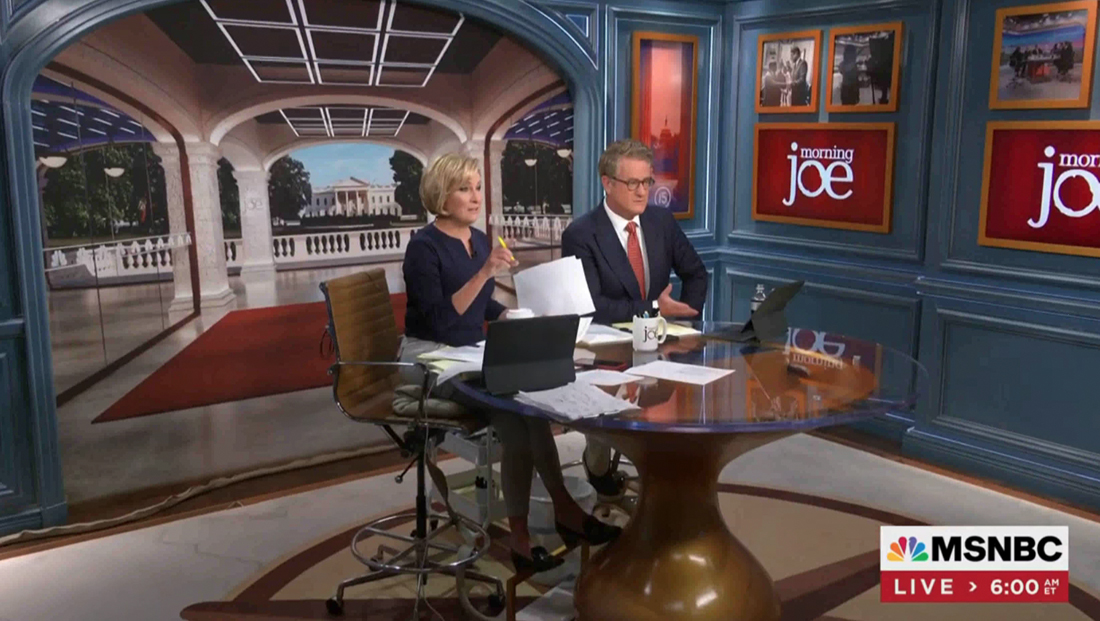

MSNBC’s ‘Morning Joe‘ originates from a variety of locations, most frequently New York, Washington and Florida. However, because it’s billed as a political-themed offering, a background of Washington, D.C. landmarks is a natural choice for behind the co-anchors. MSNBC uses a combination of techniques to make it clear the background is just that, a background. First, the images of the landmarks are depicted in a quasi-illustration style. The overly verdant grass and trees are also a suggestion that the background is meant more as an idealized view of the White House. Adding the red band with the repeating show logo also helps drive home the point the view as a backdrop.

There’s also the option of adding filters, color blends, line treatments and other design techniques over an image of something that’s real to alter it in such a way that it’s not likely to be confused as being really behind the anchor.

In this 2020 screenshot from ABC News coverage of a SpaceX launch, the live feed from the launch site is shown behind the anchors. However, by showing the view wide for at least some shots, the network is illustrating the image is meant as a background element within the larger construct of its TV3 studio.

Framing the backgrounds can also be key in providing context. Wide views of video walls depicting live feeds from elsewhere add the context that’s needed for viewers to understand the image is not meant to convey location but rather serve as a background and storytelling element.

Sometimes the inherent technical limitations of LED and video transmission also help tone down the sense that anchors are really standing in front of whatever is shown in the background.

Depending on the resolution of the video wall, quality of the camera capturing the image and how the feed is transmitted, the backgrounds can appear slightly pixellated — which, despite being a step down in terms of visual quality, can actually help enhance the notion that the image is just a backdrop.

There’s also often a noticeable difference in lighting from the studio to whatever is shown in the background.

If the talent was actually on scene, for example, one would expect the light from the window or surroundings to interact with them in some way, but often anchors are shown in the near-perfect lighting conditions possible in a full studio that isn’t as easy to achieve even from temporary studio structures erected at the scene of big events.

Other differences that will appear are variations in color temperature, levels or direction.

While most viewers know little to nothing about the science behind light, it’s often possible for the brain to compute, even subconsciously, that there is something about the picture that makes it appear simulated.

Relying on how viewers “might” perceive something, however, can be a tricky prospect, so it’s typically not best to make that the only sign that a background is simulated as far as ethical considerations go.

It can also be the absence of certain shots that reinforce the notion that talent is in-studio rather than the field.

Often when stations or networks are physically on-scene they want to drive that point home with viewers, so there are often plenty of views of the on-scene set that clearly show it is in the actual location.

Again, however, relying on the absence of such shots for ethical considerations probably isn’t, by itself, enough.

AR and VSEs

In more recent years, another layer has been added to video wall backgrounds — augmented reality and virtual set extension elements.

In its broadest sense, augmented reality involves taking an image, whether still or moving, that has elements added that are not physically there in real life.

This photograph from CBS News‘ 2020 election studio shows talent seated in front of a video wall that takes a video feed of Times Square and adds augmented reality elements to cover most of the large, electronic billboards and other advertising in the real Times Square with graphics that match CBS’s election look. The studio shown here is actually adjacent to Times Square but the windows overlooking the street were covered.

Although not purely AR in the traditional sense, some networks also use imagery based on real views, such as the Capitol, with added elements mixed in, a strategy that helps reinforce the fact that the background is not meant to be viewed as being real.

In this image of NBC’s 2018 election night set, the video wall behind the talent showcases an image of the Capitol that is likely based on a real photograph but has been heavily edited to the point where it becomes more of a backdrop. In addition, NBC added the large blue boxes above either wing that would not be physically possible.

Virtual set extensions, meanwhile, are a technique that combines a video wall with 3D or faux-3D renderings of a physical space, either real, imaginary or hybrid to create the look that there is more structural elements beyond what is actually present.

In this view of the new Florida home studio for ‘Morning Joe’ that debuted in 2022, the image in the archway between the blue walls is shown on a video wall.

Virtual set extensions are, again, typically meant only as background elements as opposed to trying to inherently represent that an anchor is somewhere he or she is not.

They often, either purposefully or simply because full-scale, highly detailed 3D models are not used to create them, have a distinctly simulated, almost video-game look to them that can help a viewer’s mind understand it might not be real.

In this image, taken during a 2019 rehearsal before CBS’s ‘Face the Nation‘ debut from the new studio it shares with ‘CBS Evening News,’ the video walls are filled with virtual set extensions that make it appear there are spaces beyond the physical set. The extensions use 3D simulations of parts of the real set as well as Washington, D.C. architectural elements to enhance the effect.

Other virtual set extensions include elements that are purposefully unrealistic or even fanciful — such as the views of Washington, D.C. landmarks used on CBS’s “Face the Nation” framed by simulated structural elements. In most cases, these views would not be realistically possible since CBS cannot build a studio that has both views from inside the Lincoln Memorial and with front-on views of the White House and Capitol without somehow ignoring the rules of space and time.

“Face the Nation” also uses an almost surreal lighting effect on its set extensions, which enhances the notion that these views are meant as background elements and not to depict actual views.

It’s also not necessarily relevant to its coverage if the studio really is near the landmark being shown assuming the background isn’t referenced as being real.

Again, virtual set extensions and AR do require viewers to have some basic understanding and sensitivity toward how things look in the real world as opposed to the virtual one. That line is likely to become more and more blurred as technology improves and concepts such as the metaverse begin to encroach on society.

Even in cases where video wall images are solely background images, it will likely become more important for broadcasters to pay close attention to how viewers might perceive these images given the increased crossovers between real and virtual.

Combining multiple applications of some of the looks mentions here is a good benchmark on how to ensure that viewers are given the context and visual cues they need to understand the difference between a background and actual locales or scenes.

Subscribe to NCS for the latest news, project case studies and product announcements in broadcast technology, creative design and engineering delivered to your inbox.

tags

AR, Augmented, Augmented Reality, CNN, virtual set extensions

categories

Broadcast Design, Broadcast Industry News, Featured, Video Walls