Column: The past and present of virtual production—and where it could go next

Subscribe to NCS for the latest news, project case studies and product announcements in broadcast technology, creative design and engineering delivered to your inbox.

When you hear the phrase “Virtual Production,” what do you envision?

Generally, we think of it as an amalgamation of real-time production techniques that combine physical subjects with digital “magic” to create eye-catching content.

But while VP has become a buzzword in recent years, it’s not entirely new. It wasn’t always known as “virtual production,” either. In fact, the earliest form of what we now call ‘VP’ happened 75 years ago in British cinema. Production designer David Rawnsley began using back projection in his ‘Independent Frame’ system, pre-planning extensive storyboards and models along with camera and talent movements. While his Independent Frame technology never truly caught on, the principles of virtual production remain the same today; using planned pre-visualization, tracking camera and talent movements, and simulating environments or assets in real time.

A recent history

However, the history of virtual production that we will focus on begins at the turn of the 20th century. Once digital editing entered the picture, filmmakers could transcode the film to digital media and edit material even while it was still being shot. This eventually evolved into on-set editing, and then into adding VFX from personal desktops. As a result, rigid feedback pipelines became agile, fluid, and accessible in real time.

A glowing blue puck was used on Fox Sports’ live ice hockey broadcast in 1996 to make the puck more visible on screen, marking the first use of augmented reality (AR) during a live sporting event. This ‘FoxTrax’ system was billed by Fox as “the greatest technological breakthrough in the history of sports,” bringing live AR into the homes of millions of sports fans.

Just a couple of years later, in 1998, an NFL live broadcast displayed a yellow line to denote a ‘first down line’ location on the field. This was quietly revolutionary. Before then, sports fans would squabble amongst themselves over whether their team had earned a first down until they heard confirmation from the commentator or referee. With this simple yellow line, the NFL changed the way we watch the game. It offered real-time feedback to viewers about the state of play in a way that not even in-person spectators could see – and marked a turning point for the use of virtual production in live broadcasts.

Later, advancements in filmmaking technologies led to the use of virtual cameras for pre-planning camera moves and simulcams, which superimposed virtual characters over live-action in real-time. Peter Jackson’s The Lord of the Rings: The Fellow of the Ring (2001) and James Cameron’s Avatar (2009) are some of the earliest examples of these VP technologies in Hollywood filmmaking.

Convergence of circumstances

After initial breakthroughs in real-time CG, AR, green-screen, and other live graphics started becoming commonplace in the late 2000s. With advancements in visual and consumer technologies, the public could have AR in their pockets – from Google Maps Live View to Pokémon GO.

Gaming technologies also improved to the point where graphics started becoming truly immersive. GPUs and graphics cards have become faster and more powerful, and game engines like Unreal Engine and Unity have made significant progress. Released by Epic Games in 1998, Unreal Engine has evolved from being a game rendering technology into a real-time graphics engine that pushes the boundaries of photorealism across industries.

As a result of these technological developments, streamed content, social media networks, and gaming apps emerged as challengers to traditional cable TV, creating a shared social experience – and mainstream content creators had to push their boundaries to keep up.

From the earliest applications of AR in live broadcast, we now see this technology used across all forms of sports broadcasting. In addition to enhancing viewer engagement like these NFL team mascots, graphics can also be used to incentivize brand investments, like this Halo Infinite x Oregon Ducks AR experience.

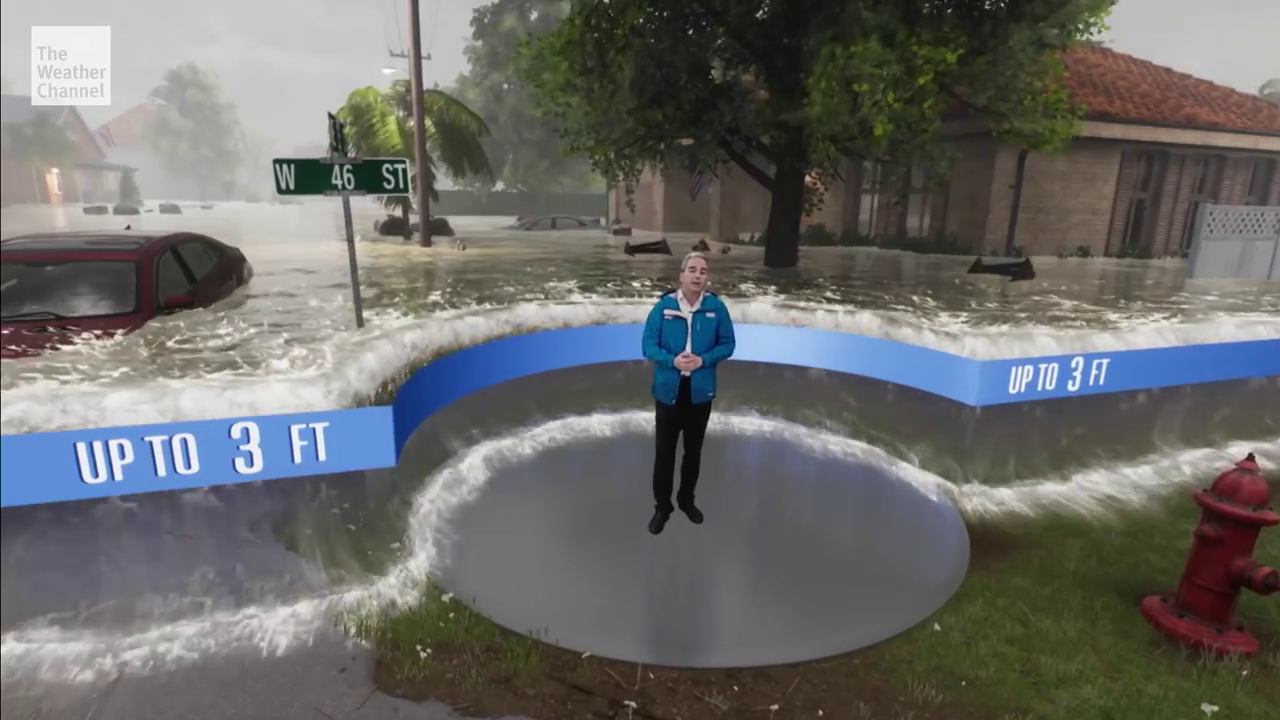

Virtual studio techniques, such as those used on the Weather Channel, can bring something as simple as a weather report to life. Viewers can be fully immersed in the current weather conditions as presenters are thrust into the middle of a storm. With live 3D graphics overlaid onto a green screen, we can watch the talent interacting in real-time with the virtual environment around them, enhancing our engagement.

The rise of XR solutions, which use large LED screens to display virtual environments controlled in real time, has made virtual production mainstream. Popularized by The Volume of The Mandalorian (2019) fame, we’ve seen LED screens used increasingly across Hollywood productions, such as The Batman (2022), as well as in the advertising world, as showcased in the Nissan Sentra car commercial.

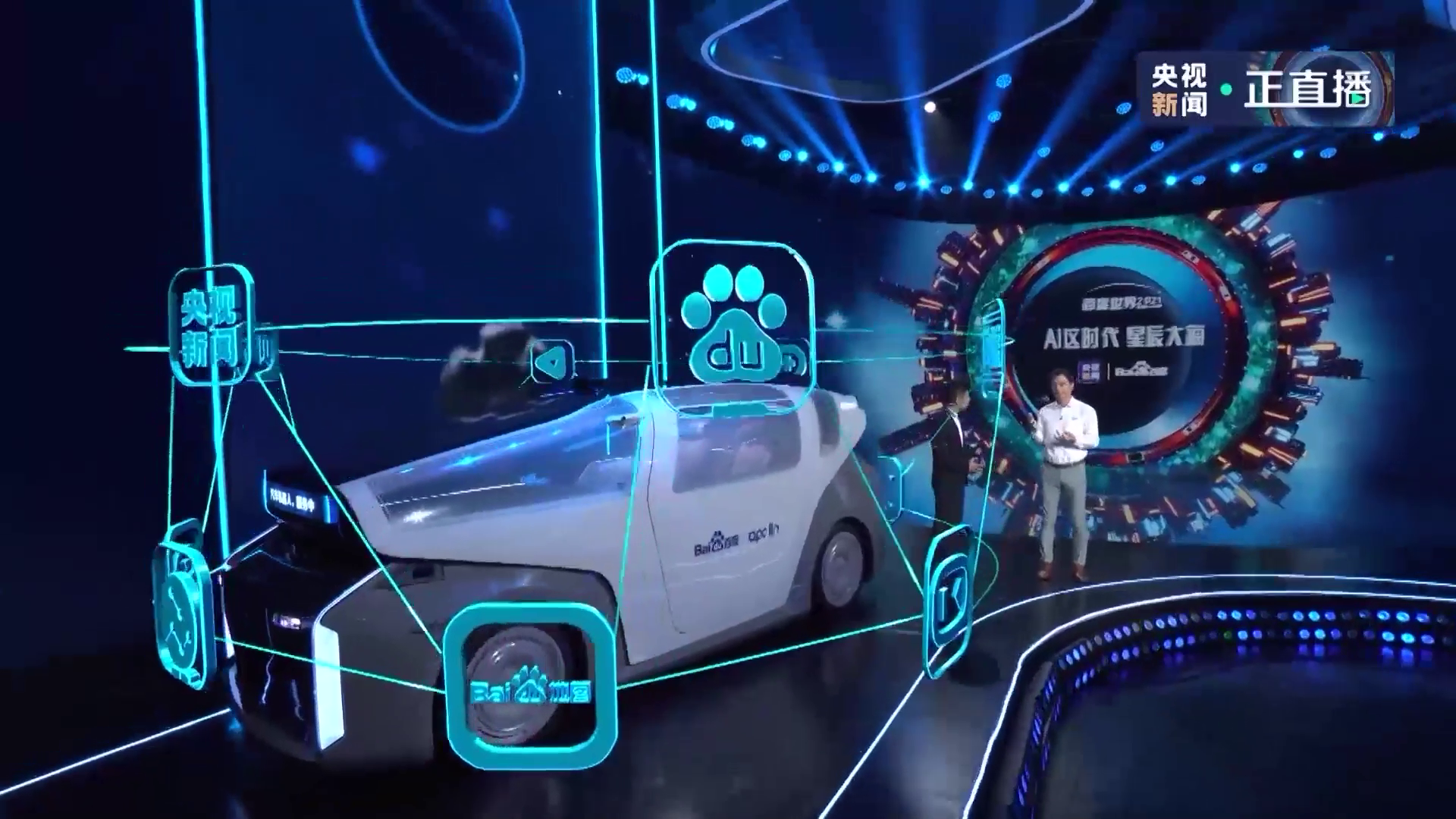

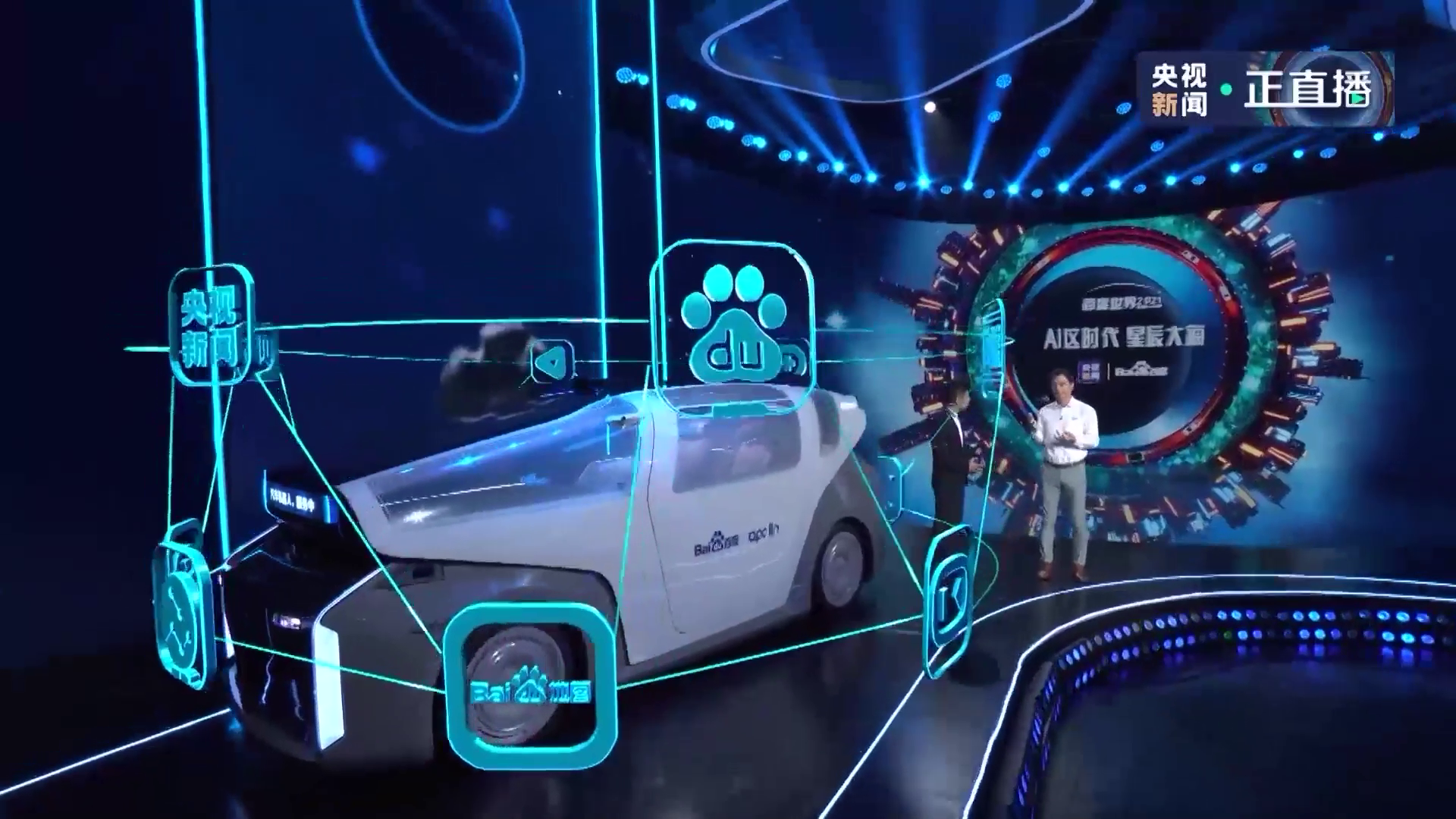

Broadcasters are also turning towards XR, with China Central Television and the BBC integrating it into workflows.

The future of media production

There is no doubt that soon, virtual production will be regarded as a standard media production.

Real-time tools are lowering the entry bar for all types of content creators outside of typical production and education environments. Ideation and creation stages are getting shorter, and hardware is becoming less expensive, which has enabled VP to become far more accessible.

We see that demand for new talent is growing with universities and other educational institutions implementing virtual production into their curricula. This is something that we are addressing with the Pixotope Education Program.

Outside of the broadcast world, use cases will vary from educational content creation, online marketing and sales, to influencers, streamers, and more. Many VFX studios have already started integrating real-time CG into their workflows, and we’re sure to see more independent studios producing content using VP. Particularly exciting for storytellers and viewers is how next-level VP techniques like real-time data input can enhance viewer engagement.

In terms of other transformative technology, we’ll likely see VP workflows move further into the cloud. The Pixotope Live Cloud, an industry first in VP cloud-based platforms, gives users a pay-as-you-go service that is always available. This enables easy up-scaling and down-scaling, helping to effortlessly create segmented content, such as developing variations of sections that employ different graphics. When anyone can create and control AR graphics live using a cell phone, it offers infinite opportunities for creativity.

But there is still more progress to be made, and VP is far from its endpoint. In the short-term, we will see advancements in hardware and software:

- Graphics cards will become more powerful.

- Complexity of systems will be reduced.

- Calibration and line-up will be simplified across VP workflows, such as for camera tracking in LED stages.

In the long-term, the evolution of AI could see it help VP workflows by acting as a virtual film crew or providing intelligence to AR asset performances and personalities.

We believe virtual production is the future of media production, and there’s no better time to take advantage of this industry shift. While there is plenty to come in the future of virtual production, current innovations and accessibility mean that it is the perfect time to take the leap into using VP in your broadcast or live workflow.

Subscribe to NCS for the latest news, project case studies and product announcements in broadcast technology, creative design and engineering delivered to your inbox.

tags

Broadcast Workflow, Epic Games Unreal Engine, Marcus Brodersen, NFL, Pixotope, Pixotope Live Cloud, the weather channel, Virtual Production

categories

Augmented Reality, Virtual Production and Virtual Sets, Broadcast Engineering, Featured, Software, TV News Graphics Design, TV News Virtual Set Design, TV News Weather Graphics, TV News Weather Graphics Systems, Voices