FCC chair signals shift toward constraining ‘national programmers’ in ownership rule review

Weekly insights on the technology, production and business decisions shaping media and broadcast. Free to access. Independent coverage. Unsubscribe anytime.

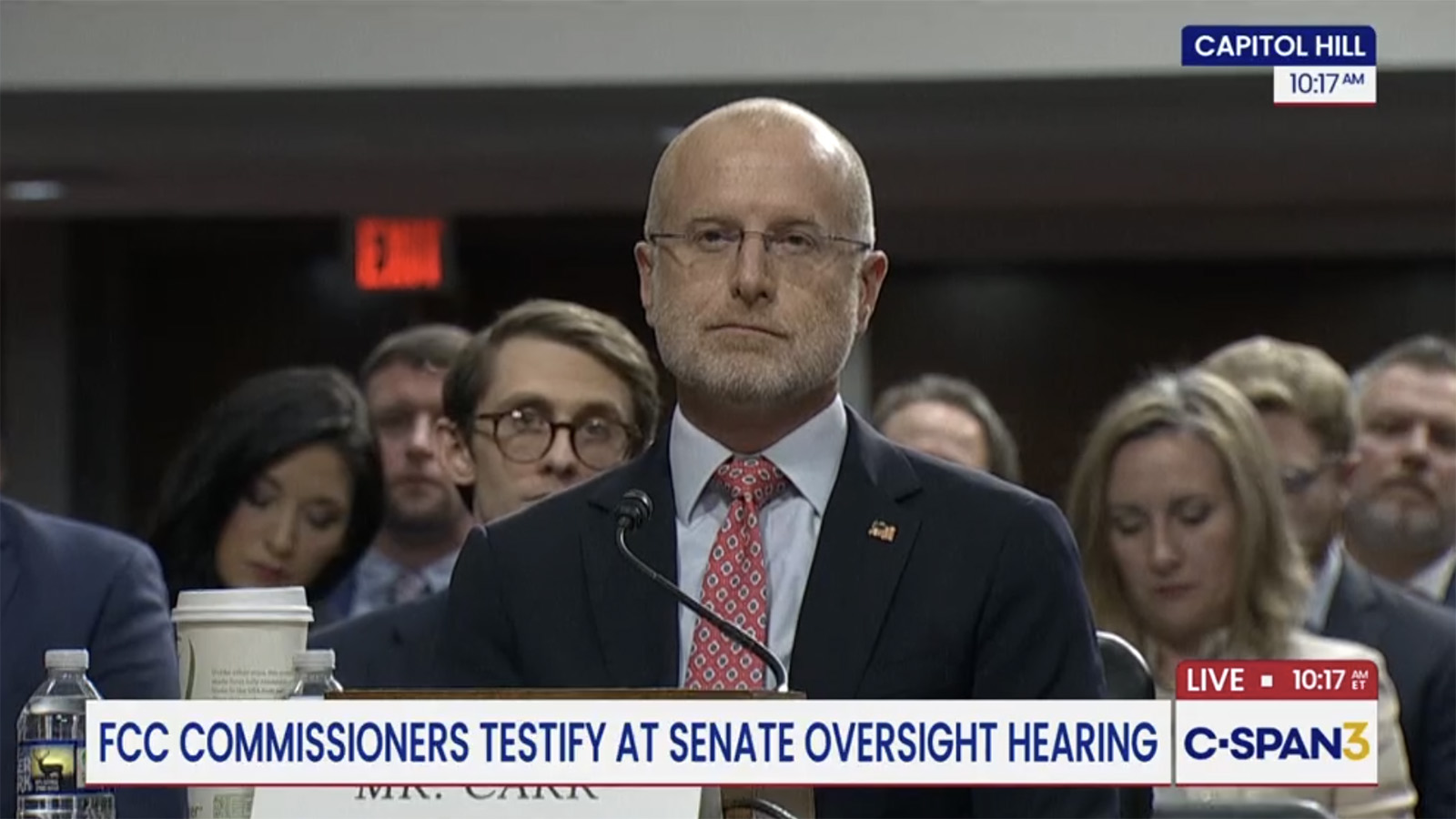

Federal Communications Commission Chair Brendan Carr said the agency has not made a final decision on broadcast ownership rules but indicated the commission is examining ways to “constrain the power” of national programming companies over local broadcast stations.

Appearing before the Senate committee on Dec. 17, Carr said the FCC is weighing whether current ownership caps serve the public interest in an era where companies such as Disney and Comcast increasingly control programming distributed through local affiliates.

“One of the concerns that I have in media policy as a general matter is you’ve got the national programmers, Comcast, Disney and others, that are increasingly dominating with respect to those local broadcasters,” Carr said. “So we want to make sure that they do have the ability to invest in local news gathering, because it’s also more trusted.”

Carr said the commission is considering how to “empower those local TV stations to reclaim more of that nightly news time for actual local news and programming” rather than content produced in New York or Los Angeles.

The comments came during a wide-ranging oversight hearing in which Carr also addressed the legal status of the FCC itself.

When pressed by Sen. Alex Padilla and Sen. Ben Ray Luján on whether the agency operates as an independent regulator, Carr said the commission does not meet the formal legal definition of independence.

“The FCC is not formally an independent agency,” Carr said, noting that commissioners lack “for cause” removal protections. “The president is the chief executive vested with all executive power in our government, and FCC commissioners do not have for cause removal protections, which means that we aren’t independent.”

Ownership rules and local news economics

The ownership cap proceeding has drawn attention from broadcasters seeking flexibility to compete with streaming services and other digital platforms.

Several senators, including Sen. Jerry Moran, have written to the FCC urging modernization of ownership rules to help local stations compete with what Moran described as “today’s media giants.”

Carr said the commission has not determined whether to expand ownership limits but suggested that protecting local news operations is a factor in the review.

“If you look at local newspapers, they’ve been shutting by the thousands all across the country,” Carr said. “And so if we care as a public interest matter about local news and local reporting, I think we have to start to look at policies that can create more incentives for investment there.”

Sen. John Curtis asked Carr to explain the potential impact of expanding the national ownership cap on local broadcasters. Carr reiterated that no decision has been made but said the commission is examining “a couple of different policies” that could affect how local stations invest in news.

Carr also said the FCC is exploring ways to require or incentivize local stations to air more locally produced content during evening hours, which are currently dominated by network programming from national companies.

Independence and executive authority

The exchange over the FCC’s legal status began when Luján asked Carr directly whether the commission is an independent agency. After Carr hesitated, Luján pointed to language on the FCC’s website describing the agency as “an independent U.S. government agency overseen by Congress.”

“Is this factual or is this a lie?” Luján asked.

Carr said the characterization on the website is “possibly” incorrect, explaining that the key test of independence under Supreme Court precedent is whether officials have protection from removal by the president.

Sara Fischer of Axios noted that during the hearing, the word “independent” was even scrubbed from the FCC’s website.

“The Constitution is clear that all executive power is vested in the president, and Congress can’t change that by legislation,” said Carr.

Commissioner Anna Gomez disagreed, saying the FCC should function as an independent regulator. “Yes, and we should be,” Gomez said when asked if the commission is independent.

Commissioner Olivia Trusty aligned with Carr’s interpretation, saying commissioners “do not have for cause removal protections, which means that we aren’t independent.”

The distinction carries implications for how the FCC approaches regulatory decisions and its relationship with the White House. Commissioners who view the agency as part of the executive branch may be more inclined to align decisions with presidential priorities, while those who view it as independent may emphasize the commission’s statutory mandate and expertise.

Public interest standard and broadcaster obligations

Carr also addressed questions about the FCC’s authority to enforce the public interest standard for broadcast licensees, an issue that has drawn criticism from some Democratic senators following Carr’s comments about comedian Jimmy Kimmel’s coverage of political figures.

Carr said broadcast television remains subject to a different regulatory framework than cable or internet platforms because broadcasters use public spectrum.

“Broadcast TV is fundamentally different than any other forms of media, whether it’s cable or podcast or soapbox or man on the street,” Carr said. “There’s a public trustee model that Congress has set up.”

When asked by Luján whether it is appropriate to revoke broadcast licenses based on viewpoint, Carr said the FCC’s role is to enforce existing rules such as those governing broadcast hoaxes and news distortion.

Gomez said the First Amendment prohibits viewpoint-based license revocations. “Absolutely not,” Gomez said. “The First Amendment applies to broadcasters regardless of whether they use spectrum or not, and the Communications Act prohibits the FCC from censoring broadcasters.”

Why it matters

Carr’s framing of the ownership cap review as a mechanism to constrain national programmers rather than simply allow more station consolidation marks a notable rhetorical shift. If the commission moves forward with policies aimed at limiting the influence of Disney, Comcast and other network owners over affiliate operations, it could reshape bargaining dynamics in retransmission consent negotiations and affect how programming costs are allocated between networks and local stations.

For local broadcasters seeking relief from ownership caps, Carr’s comments offer both opportunity and caution.

Station groups hoping to expand their footprint may find the FCC receptive to consolidation arguments framed as a response to competing national streaming services. But if the commission pursues policies that effectively pit local operators against their network partners, the result could be friction in affiliate relationships that have historically been cooperative.

Carr’s assertion that the FCC is not formally independent also has practical implications. If commissioners view themselves as part of the executive branch rather than as independent regulators, future decisions on mergers, spectrum policy and enforcement actions may track more closely with White House priorities. That could benefit applicants whose business interests align with administration policy goals and create uncertainty for those whose proposals do not.

The question is whether the commission’s stated interest in local news economics translates into concrete rule changes or remains a talking point in a broader deregulatory agenda. Broadcasters will be watching to see if the FCC follows through with specific proposals to shift programming control or simply adjusts ownership limits and moves on.

tags

Brendan Carr, Deregulation, FCC, Mergers and Acquisitions

categories

Broadcast Business News, Heroes, Policy