Oscars makes grand return with revived take on stage design, intimate camera angles

Subscribe to NCS for the latest news, project case studies and product announcements in broadcast technology, creative design and engineering delivered to your inbox.

After two years away from the Dolby Theatre due to the coronavirus pandemic, the Oscars returned home with another landmark set and a unique shooting technique that brought viewers closer to the winners.

A rendering from David Korins showcasing the 2022 Oscars set.

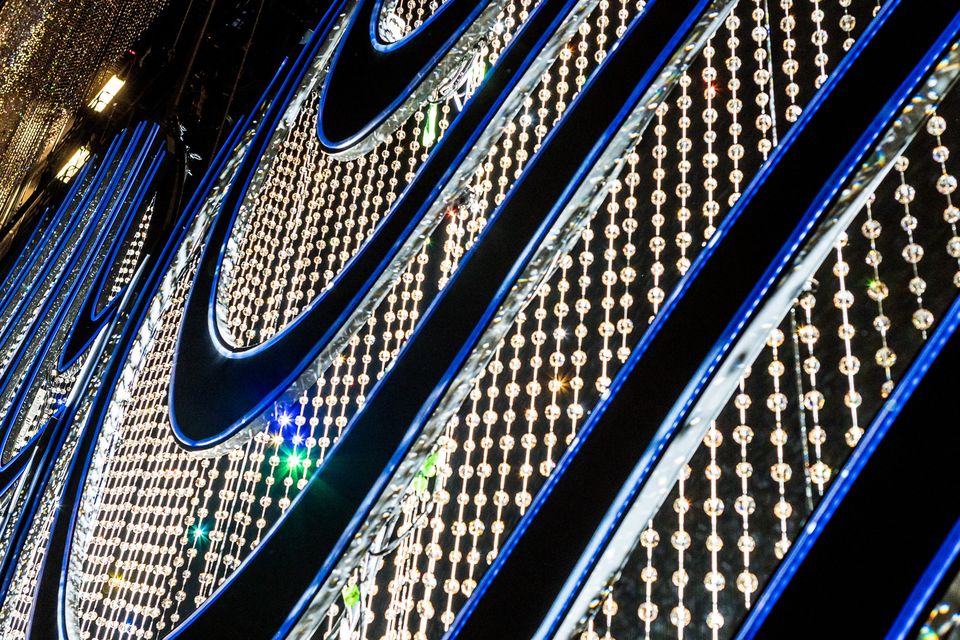

In addition to a new take on stage scenery by David Korins that is centered around dramatic curves, orbs and triangles, the stage also included Swarovski crystals for the 14th year. Similar to past usage, the crystals were strung together to fill the open spaces between dramatically curved frames used to envelop the stage.

All told, over 90,000 Swarovski crystals were used on stage.

Korins noted the stage design is meant to evoke a “dynamic portal into the future in which we trade in the currency of electricity and elegance.”

A close up of how Swarovski crystals were strung together and used to fill in spaces between structural frames. Photo by Linda Pianigiani.

Korins has worked on the Oscars previously and is also known in the Broadway set design community — and most recently created the new home for “Last Week Tonight with John Oliver.”

His design also incorporates heavy layering, with the surround and on stage elements often overlapping and intertwining with each other, creating an elegant sense of movement.

Much of this was accomplished through the use of linear elements formed from either thin elements like the crystals or neon-like LED accents installed throughout the scenery.

Korins hopes his design captured togetherness, high glamour and a hopeful tone for the future.

There were also multiple distinct looks created, which were typically used for select purposes or segments of the show. Each featured its own primary scenic motif and color scheme.

For example, the show opened with a curling “ribbon” on stage before switching to flowing circular elements and, toward the end of the telecast, straight lines and triangles.

The nods to the Oscar statuette this year featured a variety of configurations, the most notably freestanding ones created using thick segments of glass or twisted bands of metal ribbons. The number of figures appears to be reduced significantly as well.

Perhaps as a sort of symbolic gesture of trying to bring people closer together after two years of social distancing, efforts were also made to bring the action closer to both the in-person and TV audiences.

The design cut back on the number of stairs up to the stage, making the on-stage action and celeb audience members in the banquets near the front of the auditorium feel more part of the show (that proximity perhaps could have emboldened Will Smith’s now infamous on stage slap of Chris Rock).

Acceptance speeches were delivered from an oval riser with full LED floor that thrust out into the banquet and cafe-style seating closest to the stage.

In this wide shot of the Oscars stage, the robotic camera ped and lift are visible just in front of the circular platform in the center.

In addition, the Oscars opted to deploy a robotic camera pedestal and lift that was positioned close to the stage, allowing the telecast to feature a unique take on close-up shots of presenters and winners, including a different look to the push-in shots usually leveraged.

Traditionally, awards shows position the camera that captures presenters and winners fairly far from the stage — often in the middle of the audience seating or, depending on the venue, even the back of the room.

Although zooming in can obviously make up for this distance, it has a few disadvantages, namely that the camera simply “feels” farther away from the action thanks to how optics work.

Depending on the configuration and distance even slight movements by the operator or anyone on the riser that’s often built for the cameras and other crew can cause the picture to vibrate slightly on the air, which can become even more obvious the more extreme the zoom is. It can also require an extremely gentle hand to make any adjustments to the pan, tilt or zoom if the presenter or recipient moves during the telecast.

That’s where a robotic unit several feet, rather than multiple yards away from the presenters, can make an impact on the broadcast visually.

Overall, it’s one of those differences that are difficult to concretely explain — but the difference is striking. The shots of the presenters felt more up close, quite literally bringing viewers closer to the action. This camera work also brought some of the intimacy found in last year’s unique telecast from Union Station in Los Angeles.

In addition, the show also used an Agito modular dolly system and Shotover stablizer to create gentle push ins that combined vertical lift movements with optical zooms that were quite clearly being captured by a camera closer to the subject.

For the Oscars, Motion Impossible dispatched a prototype of a new product called MagTrax, according to a company spokesperson.

MagTrax enables customers to follow a magnetic strip laid on a surface, underneath a carpet, as was the case at the Oscars, or embedded within a set, according to the company.

The system allows for more advanced paths than a traditional track and the Agito will autonomously follow the embedded paths.

The straight on shot captured by the robotic camera was supplemented by views taken from different distances and angles as well, a technique that arguably brought a more cinematic feel to the show. Handheld cameras were also mixed in.

The telecast also employed a camera on wires spanning the auditorium that could be remotely controlled to capture wide, sweeping shots of the action (and at one point during the opening segment, errantly eclipsed the three hosts).

Another unique element at this year’s Oscars was the historic win by “Coda,” which follows the life of a family who is deaf and performed largely in American Sign Language.

For hearing audiences, open captions are baked into the entire film, an industry first outside of foreign language films.

Because members of the “Coda” creative team live with hearing loss, the Academy provided them with screens showing the live ASL feed of the proceedings, which was also carried on the Oscars’ YouTube channel.

Troy Kotsur walks up on stage to accept his best supporting actor Oscar followed by an ASL interpreter, who appeared emotional at times, and provided live audio of Kotsur’s acceptance speech.

In addition, when acceptance speeches were delivered in ASL, an interpreter positioned off camera was on hand with a microphone to provide audio of what the winner was signing, similar to what was done when Marlee Matlin became the first person who is deaf to win an Academy Award in 1987.

Lighting for the Oscars was led by Bob Dickinson and Noah Mitz of Full Flood.

An earlier version of this story did not fully explain the robotic camera system used for the Oscars. The story has been updated with more detail.

Subscribe to NCS for the latest news, project case studies and product announcements in broadcast technology, creative design and engineering delivered to your inbox.

tags

ABC, Agito, AGITO MagTrax, Bob Dickinson, David Korins, Dolby Theatre, Full Flood, Motion Impossible, Noah Mitz, Oscars

categories

Awards Shows Production Design, Broadcast Design, Broadcast Industry News, Featured, Heroes